Monday, December 14, 2009

Finals

And then I will cross my fingers and hope for the best. Despite all of the work I've put into this semester, I still firmly believe that any success or failure can be partially attributed to good, old-fashioned luck.

I promise thoughts, reflections and interesting research updates when I am appropriately distanced from my current work.

Thanks for reading with me this semester!

Monday, November 23, 2009

Web Review

www.annefrank.org

Designed and constructed by The Anne Frank Stichting

Reviewed Nov. 23, 2009

To young scholars across the world, Anne Frank is the face and the voice of the Holocaust. The personal confidences in her diary touch people in all corners of the globe and give the history of antisemitism a personal relevance for millions of people. The Anne Frank House recognizes her valuable contribution not only to history but to social consciousness. Because of the compelling nature of her story, the Anne Frank House designed a website that provides a moving experience, secondary only to visiting the museum itself.

The content of the website is primarily instructional. These features are primarily directed to the curious and casual visitor. In addition to discovering the basic facts about the museum, a visitor also has access to brief biographies of Anne Frank, her family, their benefactors, and the others in hiding. These biographies are enhanced with images that portray the people mentioned in Anne’s diary, their secret attic, and their surrounding community in Amsterdam. The creators of the website have recently developed the Anne Frank channel on YouTube, which provides access to interviews with witnesses of the events surrounding Anne’s life, including Otto Frank. The channel also features the only known video footage of Anne herself, in which she gazes out of a balcony, only a few weeks before going into hiding. Through the biographies, images, and videos, the website creates a unique personal connection between the visitor and Anne Frank.

The website’s most useful features cater directly to teachers and their students. The “Anne Frank Guide” is a useful tool for middle and high school teachers to use The Diary of Anne Frank as a means to teach students about the Holocaust. This page provides condensed historical information about Anne Frank and World War II in conjunction with suggested activities and lesson plans. Furthermore, the site provides unique guides for eighteen different countries, each in their own language and containing specific facts about how that particular nation was impacted by the war. The guide also takes the events of Anne’s diary out of their context and demonstrates how they can be related to present-day acts of genocide and, with equal importance, acts of humanity.

Students benefit from the interactive aspects of the website. A section on homework help allows accessible information about Anne Frank and World War II and provides a quiz. A graphic novel on the Holocaust dilutes the horrific event to an acceptable context for very young visitors. But, more importantly, the website encourages young people to relate Anne’s experience to their own life. The site has a forum for responses and discussion of the diary and its history. Additionally, the Anne Frank Tree allows guests to “leave a leaf” on Anne’s interactive monument. On a virtual leaf, a visitor chooses a theme that characterizes Anne’s legacy, such as humanity or courage, and then leaves his or her name along with a brief message or picture. These are then added to the tree, which visitors are free to peruse for inspiration.

The Official Anne Frank House website provides an educational and meaningful look into the life of an extraordinary young woman and the history that shaped her. Through its ease of use and caliber of content, it achieves a quality of experience that is rare on the internet. This website is a valuable resource for all audiences.

Digital Discord

Virginia Heffernan provides an interesting, general overview of these pro/con points in her NYT article, "Haunted Mouses." She laments that expanding accessibility to the internet is also promoting expanding accessibility to misleading information, gruesome images, and an entirely unhealthy thirst for information (regardless of its credibility). I think Heffernan is missing a crucial point-- there is a market for misinformation that has existed long before the internet. While the age of constant connectivity provides a new and tempting outlet for sensational media, we can still find tabloids at every supermarket checkout and elderly relatives relating memories that have been colored by time.

I have more appreciation for Nate Hill's criticism in "Hyperlinking Reality," in which he comments that the internet is not being used to its full potential to bring communities together. His bar code experiment attempts to counteract the isolating effect of technology by allowing members of communities to interact in a particular space, despite the differences in time, effectively creating a new kind of virtual community.

Speaking more directly at historians, Dan Cohen and Roy Rozenweig attempt to address the many questions about academic communication via the web in their online book, Digital History: A Guide to Gathering, Preserving and Presenting the Past on the Web. Cohen and RozenWeig are strong proponents of using the internet as a tool for historians and seek to advise the historical community on overcoming some of its inherent difficulties which they identify as: "quality, durability, readability, passivity, and inaccessibility." Despite these obstacles, the authors hail the internet as a new means for opening previously closed sources to a wider population and igniting a curiosity about history in the public. While I believe their book serves as an effective guide for setting up a historical website, promoting it, and perfecting it, I fail to see how they address the initial dilemmas they put forth in the introduction. For instance, they do not give any potential solutions to how the historical community can deem a site for the public credible, nor do they pragmatically address the class divide that makes the internet more available to one social class than another.

In "Wiki in the History Classroom," Kevin B. Sheets addresses one of the scariest popular sensations facing history teachers: Wikipedia. Instead of cautioning his students against Wikipedia, he used the popular "Wiki" website to allow his students to create their own page about a particular topic. Through their contributions, deletions, and edits, students learned Sheets' intended lesson: history is a conversation. And, though Sheets never mentions this, I believe that this type of lesson could also teach students to be critical of sources they find on the internet.

As I said in my very first blog post, I love the internet. I love that this week's readings cost me absolutely nothing on Amazon or the Temple Bookstore. Accessibility of information on the internet is one of the best advances to emerge from the 20th century and, hopefully, as we move forward, we will develop a societal intelligence about how and when to best use this information, both academically and personally.

Sunday, November 15, 2009

Has the moon lost her memory?

Milk provides an open window to an otherwise less accessible historical moment. The narrative, combined with the sensory experience of the film's music and camerawork, allows the viewer to feel a certain set of emotions and develop ideas in sympathy with the movie's main characters. It is overwhelming to think of the combined effort hundreds of people to produce this particular experience. But to what extent is this "synthetic memory" history?

Landsberg would love Milk because it taps into modern resources to create "universal property," making the experience of Harvey Milk and the struggle of the 1970s gay rights movement a collectively experienced historical event. She states, "These mass cultural commodities...have the capacity to affect a person's subjectivity" (146). Landsberg looks at this effect through rose-colored glasses, assuming that the producers strive to create sympathy for progressive politics. While this assumption is absolutely true in the case of Milk, I think it is also important to note that the prosthetic memories she hails could have equally isolating effects for an identity group, depending on the cultural context in which they are viewed.

In "The Generation of Memory: Reflections on 'The Memory Boom' in Contemporary Historical Studies," Jay Winter partially credits the rise of the study of memory to the rise of identity politics. He claims, "The memory boom of the late twentieth century is a reflection of this matrix of suffering, political activity, claims for entitlement, scientific research, philosophical reflection, and art."

Winter's slightly more cynical view of memory is an essential component to a thorough examination of its value in the historical community and the greater public. His recognition of the origins and nature of memory and its uses compliment Landsberg's argument in that it recognizes that memory, like all forms of history, works from an angle. No matter how effectively a filmmaker, author, song writer, museum curator, or other medium works to present a historical moment in its entirety, there will always be sympathies, prejudices, and limitations that inhibit the viewer from fully understanding the personal experience of that moment.

That being said, I agree with Landsberg that the use of technology and mass culture can provide an incomparable tool for forming a more accepting and socially progressive society, particularly at the point where more and more young people are using these mediums to acquire and develop their world view. This might be, as Landsberg recognizes, a Utopian hope, but to quote Milk:

"If a bullet should enter my brain, let that bullet destroy every closet door... And that's all. I ask for the movement to continue. Because it's not about personal gain, not about ego, not about power... it's about the "us's" out there. Not only gays, but the Blacks, the Asians, the disabled, the seniors, the us's. Without hope, the us's give up - I know you cannot live on hope alone, but without it, life is not worth living."

Sunday, November 8, 2009

How We Gonna Pay?

In "The End of History Museums, Part B," Cary Carson addresses some of the financial difficulties of museums and how various sites have addressed these problems. Carson notes that attendance at history museums has dropped drastically in recent years, depriving these museums of a primary source of income. In order to combat this, many museums have taken a proactive stance by expanding educational programs, creating visitor centers, and renting their facilities for private affairs.

Carson is extremely critical of the latter effort. He believes that the focus of history museums should be the history, not a staged event. I disagree with this perspective for two main reasons: First, the continued operation of a museum must be the primary concern of its administration and, if an event can help the museum without hurting its mission, the benefits outweigh the costs. Second, even if the historical aspect of a museum is relegated to a "sideshow" for a non-historical event, the ultimate message of bringing history to the public is still accomplished. Even in a museum's purest state, it is unrealistic to attempt to control all of the circumstances involved in a guest's experience. Ultimately, the efforts for a museum to be an event site as well as a historical site provides at least a short-term resolution to pressing financial concerns.

Even as we look at how museums need assistance from their communities, it is equally important to historically examine the communities in which they exist. Nancy Raquel Mirabal writes in "Geographies of Displacement: Latina/o's, Oral History, and The Gentrification of San Fransisco's Mission District" that economic progress in San Fransisco has rubbed out the historic and cultural roots of certain parts of the city. She hails the attempts of historians to recapture the story of the mission district by interviewing its former inhabitants and tracing the changes that have occurred in the space that they once called home. This is an extraordinary endeavor that deserves acknowledgment and imitation in similarly evolving urban areas. It demonstrates that financial success can be as damaging as financial distress.

From fundraisers and developments to ticket prices and paying the rent, it looks like even the most idealistic of public historians will never be free of the money woes.

Monday, November 2, 2009

Interpret with Love (and song?)

Tilden attempts to boil the practice of interpretation down to the essentials so that this book might serve as an instructional guide to interpreters. He relates interpretation to a teachable art, while careful to outline that, "the interpreter should [not] be any sort of practicing artist--that he should read poems, give a dramatic performance, deliver an oration, become a tragic or comic thespian, or anything as horribly out of place as these. Nothing could be worse" (55).

The above quote made me laugh, first because I recently viewed the one-woman show at the National Constitution Center, which was certainly a little tough to swallow, and second, because a certain amount of my love for history derives from musicals such as Sondheim's "Assassins" or McNally's "Ragtime". I wonder if Tilden would argue that interpretation that happens on a stage rather than a historical site would be considered art instead of history? Would "Assassins" be any different if it were performed at Ford's Theatre?

Handler & Gable, in their explanation of the difficulties of interpreting Colonial Williamsburg, clash with Tilden. Tilden gives the audience equal authority over their reception of information at historical sites, whereas Handler & Gable consider interpreters responsible for controlling the information presented as well as the means by which it is presented. They argue that history can never be presented perfectly, as sites and perspectives and knowledge are constantly changing. However, I tend to agree more with Tilden in that a well-crafted exhibit could speak to audiences not just in the present, but over a wide span of time.

Patricia West, in her discussion of Louisa May Alcott's "Orchard House" presented a wonderful way in which a historical site can be interpreted with (as Tilden encourages) love. The transformation of Orchard House into a public historical site gave the opportunity for "little women" everywhere to visit "Jo's" house and simultaneously learn about the historical context in which Alcott lived. However, West also critiques the site for refusing to acknowledge some of the more controversial aspects of Alcott's life, such as her participation in the suffragette movement. I wonder if, because this site is popular because of a work of art, Tilden would be critical of its use as a means of historical interpretation?

Little Women is also a pretty awesome musical. Just sayin'.

Sunday, October 25, 2009

Welcome to the preservation station!

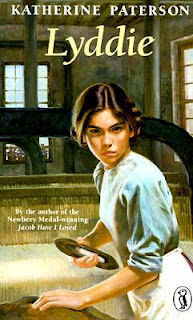

When I was about 9 years old, one of my favorite books was Lyddie by renowned childrens' author, Katherine Paterson. The story is about a young girl who flees to the Lowell mills to earn enough money to save her family's farm. Her path to success combines elements of the American dream with the cruelty of unchecked capitalism in a compelling and simple work of historical fiction. I am mildly embarrassed to admit that this novel provided my only background regarding Lowell for many years, mainly because I never had occasion to delve further into the subject.

Fortunately, this week's assigned public history reading was The Lowell Experiment: Public History in a Postindustrial City by Cathy Stanton. Needless to say, it has replaced Lyddie as my point of reference for Lowell. Stanton's analysis of public history as conducted at Lowell National Historical Park provides a multifaceted account of the background of the site, the people who preserve it, and the surrounding community. She places special emphasis on the presentation of socioeconomic issues which were the root of the shameful practices at Lowell and the reality for many people living in the surrounding community.

My favorite chapter of the book, entitled "Rituals of Reconnection" contains Stanton's research into the backgrounds and motives of the public historians at the Tsongas Center, a partner of Lowell Park. She discovers that, while these historians are largely white, educated, and middle-class, their achievement of that status is recent. Many reported a background of a lower socioeconomic status and credited their education for their class mobility. Stanton states, "For these people in 'the generation that broke the cycle,' Lowell NHP is more than just a place where they can learn more about the Industrial Revolution. It is, rather, a ritual space where they can locate themselves within changing socioeconomic realities and allay some of the anxieties involved in those changes" (168).

A similar perspective exists from the crowds of visitors who tour the park. While Lowell supposedly shows the guests "how it used to be," Stanton discovered that a large number of visitors readily connected the experiences of Lowell workers to their own lives. Union members relate to the labor movements, factory workers sympathize with the long hours, and everyone relates to the daily struggles and fears of the working class.

However, Stanton also notes that the efforts to preserve the Lowell mills as a historic site also create a dilemma by ignoring the fact that the surrounding community still endures many of the same hardships as turn-of-the-century laborers. Stanton's main critique is the rift that exists between the present day community and public historians at Lowell. She commends the efforts of public historians to bridge this gap by developing a new "Run of the Mill" exhibit which addresses modern issues surrounding Lowell and poses the tough questions about exactly how far the industry has come from its boom during the Industrial Revolution. Yet, Stanton sees this exhibit as a first step in a process that requires many more "social projects and alignments" in order to create an appropriate and productive relationship between historical sites and their public (237).

In the introduction to A Richer Heritage: Historic Preservation in the Twenty-first Century, Diane Lea also addresses this difficulty. She describes public history sites as embodying, "some of the nation's most profoundly defining ideals." Lea provides a brief history of the movement to preserve historical sites in the United States and how these movements have faced opposition in interactions with communities. Her essay emphasizes the theme and constant struggle of public vs. private ownership of history and how public historians have striven to balance this authority.

Everything seems to have gotten awfully complicated since the first time I curled up with my copy of Lyddie and learned about a place called Lowell. But the conversations of Lea and Stanton are valuable in their complexity. If there's one thing I've learned about public history this semester, it's that history and its meaning are fluid. Lowell is no longer a site with a set of facts and a simple, motion-picture-length story. It is a key component to a culture, a relationship, and an image. And those who have the responsibility of weaving these concepts together for public consumption are in for a good many finger pricks and long days bent over the loom.

And, no, I could not resist that corny textile metaphor. It was just too easy.

Monday, October 19, 2009

The Tough Stuff

It seems as though there are two types of people: those who are shocked by nothing and those who are shocked by everything. Americans, as a society, are enjoying a time when controversies of all kinds are deconstructed, repackaged, and presented in the most appealing and appalling way possible. The public is left to either embrace or reject the information, per their preconceived notions of correctness.

The subject of slavery is no exception. From recent debates on reparations to Tracy Morgan's portrayal of Thomas Jefferson, slavery has been packaged as a harrowing but defining part of American history and present day race relations. However, as slavery becomes increasingly easier to address through a modern lens, historians face a dilemma regarding their responsibilities and abilities to present slavery, simply, as it was.

James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton collected a set of essays on this significant problem in public history. Their book, Slavery and Public History: The Tough Stuff of American Memory provides a comprehensive overview of how historians and educators regularly grapple with the issue of slavery. They begin with essays that examine the broad question of how slavery has fundamentally affected modern American society. A series of essayists then examine specific instances in which slavery has been handled at sites of public history.

The authors of the essays present a number of problems, including the comfort of public history consumers (similar to the previously blogged-about Amy Tyson article), the appropriateness of museum policies, and the constant pursuit of truth. Each essay advocates the use of education to dispel the stigma surrounding discussions of slavery and encourage open and honest discourse. However, none of the contributors offer practical solutions to the specific cases that they study.

Roger Launius isolates the main dilemma of uncomfortable public history exhibits in his essay, "American Memory, Culture Wars, and the Challenge of Presenting Science and Technology in a National Museum," (published in The Public History of Science in Winter, 2007). He asks, "How might we, seeking to be useful to the society we serve, respond to this situation? How might we best survive whatever scorn arises in this process without compromising our commitment to serving society?" (30).

This question is where I hop on the mental treadmill and run over the same span of thought repeatedly. How do historians present the uncensored and uncomfortable truth without challenging the public to the point where they resent public history? Is it the responsibility of historians to be comfort counselors as well as educators?

Monday, October 5, 2009

Since we were just talking about museums...

The National Constitution Center provides a truly sensuous experience to visitors. The architecture, designed by Pei Cobb Freed & Partners, reflects the museum’s theme of continuity. The large circular room which hosts the museum’s permanent exhibit, “The American Experience” takes guests on a journey through the history of the Constitution through a series of interactive and engaging displays. The walls curve almost imperceptibly around the guests as the follow the exhibit from the signers of the Constitution to the election of Barack Obama and suddenly find themselves back at the beginning, demonstrating the incomparable, lasting significance of the Constitution.

The entrance to the exhibit is called the “Signer’s Hall,” a plain but stately space, filled with life-sized bronze statues of the signers of the Constitution, as though they were frozen in time. In the center of the room is a large copy of the constitution with an invitation for visitors to sign their own name. This reenactment of a historically significant moment effectively launches the visitor experience to the larger exhibit of the Constitution.

The exhibit itself is accessible to a wide audience. The informative and slightly controversial nature of the displays appeal to a range of adults (particularly American adults) and the fun, interactive displays successfully entertain children while providing subtle education. The exhibit moves chronologically, focusing on times in American history when the Constitution played a significant role in changing and developing law and society. The displays on the museum’s outer walls are colorful, filled with bold images and artifacts, intermingled with language from the Constitution. These are accompanied by text which provides relevant background information about the subject. Several portions of the exhibit also have a video display that can be listened to through headsets. Some videos contain historical television footage of key events, such as the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Others show commentary by modern political leaders or mock debates about past controversies.

The inner area of the museum boasts several more interactive stations that focus mainly on allowing the audience to become active participants in the history of the Constitution. A simulated voting booth allows guests to vote for their favorite presidents (unfortunately, they are compelled to choose from a short list). A display about the Supreme Court features the opportunity to try on a judicial robe and sit behind a judge’s bench. Perhaps most engagingly, throughout the museum, there are walls with large questions such as, “Should same-sex marriage be legal?” Next to these walls are stacks of Post-It notes and pencils, inviting participants to jot down their opinions, post them on the wall and, in a small way, become part of a topical national conversation.

The final segment of the museum’s permanent exhibit is a 4-D performance called “Freedom Rising.” The theater is in the center of the museum. As audiences wait to be seated, they are invited to circle the theater and view small artifacts from 18th century America, including children’s toys, clothing, and household goods. A mural depicting a Philadelphia street surrounds them and hidden speakers play snippets of staged conversations and sounds from the street scene on the painting. Inside the theater, audience seats are on a raised platform on the outer edges of a cylindrical room. A screen extends around the top half of the room. As the lights dim, a single performer enters the room and delivers a dramatic monologue about the Constitution, its creation, and its enormous impact on the evolution of the United States. Her performance is accompanied by a stunning visual production projected on the screen surrounding the room, as well as on a cylindrical screen that drops from the ceiling minutes into the show. Sound clips, some staged and some historical, complete the experience. The content of the show is a heavy dose of American pie but, based on observed reactions, this unique portion of the exhibit communicated successfully with its audience.

It is unsurprising that the National Constitution Center takes on an overwhelmingly patriotic tone and glosses over any serious Constitutional criticisms. The museum was founded as part of the Constitution Heritage Act of 1988 and two former presidents sit on the Board of Trustees. The building of the museum was initially state funded and was also given a substantial endowment. (Admission costs, a store museum, parking fees, facility rentals, and a cafe contribute to the operating costs of the Center.) However, despite the obvious financial ties to the state, the National Constitution Center maintains that it is an independent and non-partisan organization with a purely educational mission.

The National Constitution Center strives to provide a number of venues for education, from school tours to teacher resources. This mission is furthered by the museum’s continual efforts to offer free lectures and events for the public. Each month, they invite new speakers to deliver addresses on a variety of topics. These open lectures draw huge crowds and the museum hopes that their presence will lead to an increased awareness of the Constitution. Additionally, the National Constitution Center hosts a variety of traveling exhibits, most recently a tribute to Princess Diana, entitled, “Diana: a celebration.” New, rotating exhibits allow for constantly renewed interest in the museum and encourage repeat visitors. Furthermore, the National Constitution Center’s website (www.constitutioncenter.org) boasts extensive information about the Constitution for adults and several games and interactive pages for children. The Center’s dedication to education is shown through the variety of means in which its collection is accessible to the public.

The National Constitution Center exceeds expectations in terms of fulfilling its purpose of bringing awareness to the Constitution and constitutional issues in the United States. Its sensational multimedia approach, combined with elements of living history and traditional displays, successfully engages the public with some of the most notable constitutional debates over the last two-hundred years. The interactive nature of the exhibit, particularly the museum’s continual requests for guest involvement, provides visitors with a uniquely personal connection to the Constitution and a memorable experience. The National Constitution Center takes the traditional Philadelphia walking tour out of its purely historical context and creates an exciting, relevant experience for any audience.

Sunday, October 4, 2009

Museums: Who, What, How, and Why?

Which brings me to slavery.

In her article, "Crafting Emotional Comfort," published in Museum and Society, Amy Tyson writes about two separate museums and how they address the history of slavery. Conner Prairie, in Fishers, Indiana, hosts an after-hours role-playing session entitled, "Follow the North Star." As part of this museum experience, guests are led on a 90 minute simulation of the Underground Railroad in 1836. The primarily white visitors morph into runaway slaves and endure dehumanizing treatment from the museum staff. For the psychologically delicate among the participants, everyone is given a safety sash that can be waved, should anyone need to escape the escape.

Tyson also examines Fort Snelling in St. Paul, Minnesota, where the topic of slavery is, at best, removed from sight. She notes that no re-enactors portray the black slaves who worked for Colonel and Mrs. Snelling. Moreover, when the subject of domestic labor is mentioned during tours, the guides refer to bonded women as "servants," taking no notice of their race or lack of freedom.

These two polar approaches to addressing slavery show a common thread in the museums' methods of customer service: comfort. Tyson underscores the fact that both museums take extraordinary precautions to ensure that their visitors feel emotionally at ease throughout their museum experiences. At the conclusion of the article, Tyson determines that the necessity of customer care in living history museums suggests a unique dilemma and suggests that historians of all kinds, "consider the extent to which the expectation of and preoccupation with emotional comfort has entered our own terrains" (258).

Stephen Weil addresses this question and many others in his book, Making Museums Matter. He provides a comprehensive study of the history, purposes, methods, and success of museums. His analyses enlightens the reader to the infinite decisions involved in creating and maintaining a museum that benefits its community. Like Tyson, Weil looks at museums with a critical eye and aims to provide a series of objective criterion which evaluate the quality of any given museum. He suggests that, one day, museums as a whole might have to defend their worth and he wants to be prepared.

The American Association of Museums 2008 Annual Report falls in line with Weil's concern. The report indicates new plans to bring agenda of museums to Capitol Hill and ensure the success of legislative efforts that benefit museums. Additionally, the AMA aims to raise itself to well-recognized "expert" status, to improve visibility. Perhaps these endeavors will succeed in accomplishing what Weil suggests: proving that museums have both aesthetic and commodified worth.

All of this weeks' readings cast into sharp light the difficulties facing museums and those who operate them. However, the attitude toward these problems is unabashedly hopeful. The authors recognize that museums must change to meet the evolving needs of their communities and, through their careful studies, present reasonable means to enact and evaluate these changes.

Friday, October 2, 2009

Counterculture Cures

Comfort history is the fun stuff. Instead of making us think, "Oh my, how significant this is in the historiography of the subject," it makes us grin and say "Cool!" Of course, comfort history is different for everyone but for me it's 1960s American counterculture.

This is actually very convenient, since I have recently embarked on a project for my cultural history research seminar about The Living Theatre, an experimental theater group founded in 1947 which, in the '60s, converged with the counterculture and produced fascinating and provocative art.

-What do you want?

-To stop wasting the planet.

-To stop dying of competition.

-To do useful work.

-To get to know God in his madness.

-To make the destination clear.

- The Living Theatre, "Paradise Now"

For the moment, however, I'm savoring my favorite part of any writing assignment: the research. It's like directing a film, as I start to put together all of the pieces of the scenery, cast the extras, understand the plot, and glean motives. I especially enjoy celebrity cameos-- I got quite a thrill when I read a bit of a diary that revealed an affair between one of the Living Theatre founders and Abbie Hoffman!

And now I think it's time for another cup of tea, a new box of tissues, and another juicy counterculture memoir. Their road to revolution is my road to recovery!

Sunday, September 20, 2009

The Significance of Mad Men (and Reading Commentary #2)

Some people would call me a television junkie. I prefer to think of myself as a connoisseur of fine viewing. That being said, tonight was a big night for junkies and connoisseurs alike as we all celebrated another fine year of programming with the 61st Annual Primetime Emmys.

While I would love to diverge into a discussion about the best and worst dressed (Mariska Hargitay and Sarah Silverman, respectively) and my misgivings about certain winners (Breaking Bad winning over House? Seriously?), my thoughts are turning more toward a certain "Outstanding Drama" winner: Mad Men.

Mad Men, a program about the personal and professional lives of ad agents in the early 1960s, has captured the interest of America in a unique way. This colorful depiction has led to New York Times articles analyzing character's drinks, fashion designers creating '60s throwback clothing named after the characters, and a number of nostalgic written works by people who remember the Madison Avenue scene in the '60s.

In light of this week's Public History readings, I have been thinking about the public's particular fascination with a program so steeped in history. Rosenzweig and Thelen argue in The Presence of the Past that the public has an extremely intimate connection with history. In an extensive survey conducted, most respondents stated that they believed that history presented alternatives to the present. In their own narratives, participants reflected mainly on change that has occurred and how changes impacted the present. It seems reasonable, then, to assume that the interest in a historical (albeit fictional and dramatized) program derives from an interest in the vast cultural differences between "then" and "now."

Interestingly, Rosenzweig and Thelen also discovered that most of the surveyed people ranked television as one of the least reliable means of obtaining historical information. The commercialization of the programs has embedded a (not entirely unjustified) cynicism in the public that overrides some of the potential to glean facts from fiction. However, when surveyed about the frequency of interaction with history, watching a historical movie or television program was second only to looking at and taking photographs.

Further research conducted by Kim Hyounggon and Jamal Tazim illustrates a deeper connection between people and their history. They followed the experiences of frequent attendees at Renaissance Fairs and their quest for existential authenticity. They form an entirely new self-identity in an accepting environment as a means of interacting with history. In a way, they are doing to a much more complicated extent, what historical television does for millions: enabling them to connect to (and perhaps escape to) a time and a place with which they have a personal or emotional connection.

In fact, I think Mad Men's leading man, Don Draper, explains it best:

"There is the rare occasion when the public can be engaged in a level beyond flash- if they have a sentimental bond with the product...It takes us to a place where we ache to go again."

(I'm sorry I can't embed the video. Apparently that would violate copyright laws. But definitely click on the link. It's well worth it.)

It is this cultural bond along with a desire to communicate history that led Michael Frisch to propose the idea of a Philadelphia "Historymobile" which would collect personal memories and turn them into historical Philadelphia exhibits that would travel the city, allowing its members to contribute and experience history in a festival-like atmosphere. The idea never came to fruition, due to lack of funding, but the idea is based on the theory proven by Rosenzweig and Thelen, that people want to be connected to their history.

Drumming up an avid following of Mad Men probably isn't the best way to bridge the gap between scholars and the public with regard to history. Let's face it-- the sex appeal probably shares equal responsibility with the history for the show's popularity. But the variety of reactions to the program shed light on the fact that the public is interested in the past, especially when the past holds a personal connection to their present. And I think it is a valuable use of time to discern where public history and popular history can converge to best communicate with their audiences.

Maybe make Don Draper the new face of the AHA? Seriously, that man can sell anything.

[Image courtesy of Subthemag.com. Stable URL: http://subthemag.com/tss/wp-content/uploads/2008/07/men_wideweb__470x2880.jpg]

Sunday, September 13, 2009

Reading Commentary #1

> Historians in Public: the practice of American history, 1890-1970 by Ian Tyrrell

> An excerpt from The Lowell Experiment by Cathy Stanton

> An American Historical Association Presidential Address by Carl Becker entitled, “Everyman His Own Historian”

All three sources presented a slightly different perspective on the role of how scholarly history functions in the public. Tyrrell’s account demonstrates the ways in which historians have attempted to bring their work to the public over several decades. He refers to the process of “doing history” (a phrase new to me until this class) as the conscious attempt of historians to present history in an accessible fashion. To this end, historians have worked to present their craft through a myriad of mediums including radio, film, text, and schools. Unfortunately, as Tyrrell notes, these attempts have yielded few results. These roadblocks have not, however, prevented historians from progressively broadening the field of history to include previously ignored peoples or events. While historians have a difficult time finding a market for their scholarly work, over time, their efforts quietly end up embedded in popular culture, politics, and daily life.

Cathy Stanton's approach toward history is accessible to the public because it derives through the public. Her approach of analyzing the information provided in the tours of Lowell National History park and offering her own research in conjunction to the park's provides a unique interpretation of the city. Stanton attempts to, "underscore the performative, contingent nature of all historical interpretation" (xiv). Like Tyrrell, she sees the role of the historian in as an inherently public position with a responsibility to a particular audience.

Carl Becker takes this approach one step further, outlining the importance of "Mr. Everyman" and his experience in living history. He weaves a story of a man whose experience of life is, essentially, different from the history of his life. In this way, Becker draws the conclusion that there are two types of history: the actual and the reported. He tries to find a point where the two converge and, though it appears futile, he urges historians to not disregard the importance of actual history. He views this as the obligation of historians to be as accurate to the experiences of the past as possible given what he feels are extremely limited resources.

And because you, dear reader, have made it to the end of this somewhat dull post, I would like to leave you with a hint of an amusing image direct from my own living history:

Faculty vs. Student softball match.

Monday, September 7, 2009

Women Can't Fight: Redux

Thursday, September 3, 2009

Buon giorno!

- I have been to Italy, France, China, the Netherlands, Malta and, most importantly, Canada.

- I watch too much TV. I especially enjoy Mad Men, House, and 30 Rock.

- I am an enthusiastic spectator of musical theater.

- I bought my first car last year. Well, technically, I think the bank still owns most of the car, but I drive it. Its name is Abbie.

- I am a long-distance member of the world's best book club, called the "Uppity Women." Hence the title of this blog.